|

For a few words about my

reviewing process and preferences, please see the introduction to

Classical Reviews # 36.

|

| SIBELIUS VIOLIN CONCERTO SINDING

VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1

HENNING KRAGGERUD, VIOLIN

BOURNEMOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, BJARTE ENGESET

NAXOS SACD/CD HYBRID 6.110056 AND DVD-A 5.110056

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

The world's best-selling classical record label, which for quite some time

threw its weight behind DVD-Audio by occasionally issuing recordings in both

redbook CD and DVD-Audio format, has now also embraced SACD hybrid

technology (discs playable on both SACD and conventional players) and

released its new recording of the Sibelius Violin Concerto in both DVD-A and

SACD formats. The DVD-A offers 5.1 Dolby Digital AC-3 and DTS Surround,

while the SACD (recorded with the DSD process) offers options of two-channel

CD and SACD as well as 5.0 SACD Surround.

For those like myself who continue to enjoy two-channel stereo, the good

news is that this is a wonderfully performed and recorded version of the

Sibelius. The soloist, Norwegian violinist Henning Kraggerud, is a winner of

Norway's Grieg Prize. Playing the Guarneri del Gesù “Ole Bull” violin of

1744 with its only existing extra-long violin bow, he produces unfailingly

lovely tone. The low tones, while perhaps not as meaty as those generated by

the Stradivarius Maxim Vengerov plays on his competing recording of the

concerto, are rich and full, while the highs are pure and sweet.

Emphasizing the lyrical aspects of Sibelius' concerto, Kraggerud eschews

excessive vibrato and big dramatic gestures to focus on the so-called

“dark,” brooding beauty of Sibelius' melodically lush landscape. With his

highest goal that of serving the music, Kraggerud's plaintive performance

draws less attention to technical perfection and effect than to the

extraordinary beauty of the writing. The opening is gorgeous, Kraggerud's

heart-touching phrases supported by the resonant entry of truthfully

recorded trumpets, cellos and percussion.

The playing in middle movement adagio again seems intentionally restrained,

the soloist avoiding showy, singing highs in order to emphasize the forlorn

beauty of the writing. After letting loose in the movement's grandly

romantic conclusion, Kraggerud performs the final allegro at a notably fast

pace. (If you don't know this concerto, the opening melody of the final

movement is unforgettable). Everywhere the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

proves at one with the soloist, providing full accompaniment with

unfailingly lovely tone.

By contrast, Vengerov's Telarc recording with Daniel Barenboim and the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra may be far more detailed, but the technique

constantly draws attention to itself. Sibelius' concerto becomes a series of

grand flourishes, with startlingly dramatic bites into the strings,

exclamation points at the end of soaring phrases, and an overall approach

that seems far more suited to Russian drama than Nordic romance. Barenboim's

equally overblown approach to orchestral interludes would serve Wagner well.

The other works on Kraggerud's program provide nice counterpoint. Sibelius'

Serenade in G minor, Op. 69b: Lento assai and Christian Sinding's Romance in

D major, Op. 100 offer many moments of loveliness. Sindings' First Violin

Concerto is far more Germanic sounding than Scandinavian; hardly in the same

league as the Sibelius, it's definitely pleasant listening fare. Meatier

companions would have been welcome, but Naxos' bargain price leads to a

strong recommendation. That the performances have been issued in the new

high-resolution hybrid SACD and DVD-Audio surround sound formats is a

definite plus. On highly affordable entry-level multi-format players, this

disc sounds light years better than standard CD.

|

THE CHILL OF SCHUBERT'S FINAL WINTER

JOURNEY

FRANZ SCHUBERT: DIE WINTERREISE

IAN BOSTRIDGE & LEIF OVE ANDSNES

EMI CLASSICS 7243 5 57790 2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| FRANZ SCHUBERT: DIE WINTERREISE

MATTHIAS GOERNE & ALFRED BRENDEL

DECCA 027846 70922 1

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| FRANZ SCHUBERT: DIE WINTERREISE

NATHALIE STUTZMANN & INGER SÖDERGREN

CALLIOPE CAL 9339

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Franz Schubert survived only one winter between completing the first

version of his song cycle Die Winterreise (A Winter's Journey) and dying in

November 1828 at age 31. If the cycle's virtually unrelenting gloom and

despair mirror the realities of his slow and painful decline from the

syphilis he contracted as a teenager, its profundity has led to its

ascendancy as one of the great expressive vehicles for voice.

Schubert had already published his 1823 tenor song cycle Die schöne Müllerin

(The Lovely Maid of the Mill,) to poems by Wilhelm Müller when in early 1827

Franz von Schober drew his attention to a cycle of twelve additional poems

by Müller entitled Die Winterreise. Schubert immediately began setting them

to music, completing his work in February. It was only in autumn 1827, after

their publication, that Schubert discovered that Müller had subsequently

published an additional twelve Winterreise poems and issued all 24 in a

newly arranged sequence.

Schubert promptly began setting Müller's additional 12 poems, thereby

creating a cycle of 24 songs. He was still correcting proofs of the complete

edition on his deathbed.

Müller, who dedicated his Winterreise poems to composer Carl Maria von

Weber, had once stated that his poems led only a half-life “until music

infuses them with the breath of life.” Their discovery by his contemporary

Schubert thus served as an ultimate wish fulfillment. Sharing the composer's

karma, he too died young, in the autumn of 1827 at age 33, probably unaware

that Schubert had set his songs to music.

A number of contemporary accounts of Schubert's creation of Winterreise

survive. According to his friend Josef von Spaun, "For a time Schubert was in a melancholy mood and seemed to be rather ill.

When I asked him what the matter was he simply replied, ‘Well, you will soon

hear and understand it is all about'.”

Soon thereafter, Schubert invited von Spaun to Schober's house to hear the

“frightful” songs that “have made me suffer more than my other songs. He

then sang to us in a trembling voice the whole Winterreise. We were

completely taken aback by the gloomy mood of these songs, and Schober said

he had liked only one song, ‘Der Lindenbaum'.”

The history of contemporary Winterreise performance is so closely associated

with a legacy of baritone recordings that extends from Gerhard Husch through

Hans Hotter, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Matthias Goerne (with the

addition of an incomparable version from soprano Lotte Lehmann) that it is

easy to overlook that the cycle was originally set for tenor. The actual

range designation seems not to have been crucial in Schubert's mind. He had

downwardly transposed three of Winterreise's songs for either baritone or

contralto at the time of his death, and had previously dedicated his tenor

cycle Die schöne Müllerin to baritone Baron von Schönstein. What Schubert

considered primary was the energy singer and pianist brought to his songs.

Performing the cycle is no easy task. Besides the vitality and focus

necessary to sustain a performance that can last over 80 minutes, the

ability to imbue Schubert's frequent strophic repetitions with interest

demands artistic integrity of the highest order. You can alter tone and

dynamics in thousands of different ways, or vary tempo until hell freezes

over, but if your performance does not transcend technique to transport the

listener to a state of universal identification with the protagonist's

plight, the interpretation falls short.

Tenor Ian Bostridge and pianist Leif Ove Andsnes (EMI) have just recorded

the songs, paving the way for European and U.S. performances. Their

recording adds to a discography that includes tenors Peter Schreier, Jon

Vickers, Bostridge's fellow Englishman Peter Pears, and most recently

Christoph Prégardien. If the 1963 pairing of Pears and his life-companion

Benjamin Britten (Decca) continues to reign supreme, perhaps illuminated by

an inner identification with the suffering Schubert had no choice but to

voice in heterosexual terms, the modern version from Bostridge and Leif Ove

Andsnes offers far more beautiful sounds.

Having said that, I confess that Bostridge and Andsnes leave me cold, and

not in the way Schubert intended. Certainly Bostridge possesses a most

beautiful voice. Guided by great intelligence, his instrument retains the

freshness and ease of youth. When, as in the last verse of the first song,

he intentionally and sparingly softens his instrument to emit caressingly

sweet sounds, his singing possesses a pathetic fragility that goes straight

to the heart.

Elsewhere, however, the tendency to underscore words with pregnant emphasis

seems more precious than genuine. Especially when the tenor veers over the

top with emotion, bespoiling songs such as “Der greise Kopf” (The hoary

head) with a near hysteria that seems far more appropriate for Salomé than

Schubert, I find myself parting company. With his “listen to how important

this word is” approach continuing through the final, deathlike song,

Bostridge seems guided more by his thoughts about Schubert's music than an

emotional identification with it.

No one knows exactly what tempos Schubert wished for the songs, nor how much

freedom his chosen singers took with rests and phrasing. Bostridge and

Andsnes play it safe, offering a “modern” interpretation. Tempi are pretty

even, save for the occasional and welcome ritard. The freedom we hear in

older lieder recordings is rarely in evidence. Where Britten's genius

consistently illuminates Schubert's piano line, underscoring phrases that

either answer the singer or set the primary tone, Andsnes chooses to contain

himself, a wise move considering Bostridge's over-emoting. There is some

beautiful bell-like tone in “Die Krähe” (The Crow), but for the most part,

this is Bostridge's show, with Andsnes providing sober balance.

For contemporary interpretations, I find myself turning to two other new

recordings. The first, capturing Matthias Goerne and Alfred Brendel live at

Wigmore Hall (Decca), has already received much critical acclaim. To these

ears, their interpretation is far more nuanced than Goerne's recent

extraordinary live San Francisco performance of Winterreise with Eric

Schneider. The voice is gorgeous beyond belief, moving between profound

baritone rumbles of despair and higher, melting tones. More important, the

singing and playing seem to spring from a genuine sympathy with the work.

This collaboration constantly reaches inward to the core pulse of despair.

Equally essential, moreso for receiving little attention is contralto

Nathalie Stutzmann's shattering performance with pianist Inger Södergren.

Hearing Stutzmann's rich, soulful voice convey the essence of Schubert's

suffering makes one mourn that the fallout from 9/11 prevented her from

flying to San Francisco in 2002 to record Mahler's Kindertotenlieder with

Michael Tilson Thomas.

Stutzmann's recent Vivaldi performance in Berkeley revealed her wearing a

tasteful, iridescent gray pantsuit set off by high-soled, lace-up patent

leather shoes so emphatically masculine that I can imagine Gertrude Stein

trading of one of Alice B. Toklas' precious recipes for a pair. Stutzmann's

heart-rending timbre and uncommon freedom with nuance and tempo make the

recording one to treasure. Some of the songs are taken so slowly that only a

great artist with unfailing concentration – a gift Goerne shares -- could

render them so riveting. The voice does occasionally approach shrillness in

more emphatic passages, but the overall beauty of the interpretation,

constantly infused with heart-touching tones of suffering, makes this a

performance to own.

|

| JAMES GALWAY: WINGS OF SONG JAMES

GALWAY, FLUTE AND TIN WHISTLE; JEANNE GALWAY, FLUTE, MORAY WALSH,

CELLO SOLO

LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHSTRA, KLAUSPETER SEIBEL

DG B0003024-02

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Sir James Galway's latest release augments a huge discography that fully

documents the 65-year old flautist at the height of his powers. If Wings of

Song: Popular Classical Melodies for Flute and Orchestra, his first disc for

Deutsches Grammophon since his old days performing as principal flute with

Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic does nothing to enhance his

reputation, it certainly attests to the across-the-board popularity he has

achieved.

Although Wings of Song undoubtedly takes its name from Felix Mendelssohn‘s

evocative song Auf Flugeln des gesanges (On Wings of Song), that selection

is curiously absent from the album. Instead, we have a mix of such soothing

classical stalwarts as Maurice Ravel's Pavane pur une Infante défunte, Eric

Satie's Gymnopédie No. 3, an adaptation of the 2nd movement of Joaquín

Rodrigo's “Concierto de Aranjuez,” the 1st movement Siciliano from J.S.

Bach's Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord No. 4 in C minor, and an

arrangement of the 2nd movement from Antonin Dvorák's String Quartet No. 12

in F major “American,” with a number of opera arias and classical art songs

thrown into the mix.

As the Voice of Woodstock whistling Puccini in the Emmy-nominated televised

Peanuts cartoon, She's a Good Skate, Charlie Brown, I hesitate to criticize

transcriptions of opera for instrument. Yet it must be acknowledged that

anyone hoping for the passion and exalted spirit associated with such arias

as Camille Saint-Saëns' “Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix,” Vincenzo Bellini's

“Casta diva,” Christoph Willibald Gluck's “Che faro senza Euridice?” and

Richard Wagner's “Der Engel” has another story coming.

The pearly, ultra-smooth sound of Galway's flute certainly conveys the

loveliness of these arias, but melodic sweetness is only one of the reasons

they are treasured. The other is because they serve as supreme vehicles for

the expressive powers of the human voice. If Galway's flute can achieve such

a level of expression – there are hints of passion in the Rodrigo excerpt –

it certainly falls short in opera. The tone may be beautiful, but the

performances are placid. Delilah could never seduce Samson with such

languor. To call the playing “pretty” pretty much says it all.

Where Galway does excel is in the duet with his wife Jeanne on Jacques

Offenbach's beloved Barcarolle -- music that perfectly suits the dreamy

tenor of their playing -- and Howard Shore's A Lord of the Rings Suite

written expressly for Galway's talents. Galway's rendition of John Denver's

“Annie's Song” also scores in spades, as do the more serene of the classical

instrumental adaptations. As for Craig Leon's soppy introduction to Franz

Schubert's “Ave Maria,” you don't want to know from it.

|

| CHANTICLEER: HOW SWEET THE SOUND

SPIRITUALS AND TRADITIONAL GOSPEL MUSIC WITH BISHOP YVETTE FLUNDER

WARNER CLASSICS R260309

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| TRANSCENDENCE GOSPEL CHOIR:

WHOSOEVER BELIEVES AMOR

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

“God has no respect of persons” was a phrase I heard over and over in the

summer of 1965 as a civil rights worker in North Carolina's Martin County.

Almost 40 years later, when the Democratic National Convention's

representatives for the first time accurately reflected the rainbow

composition of our society, white people are daring to embrace music usually

performed by African-Americans. From German baritone Thomas Quasthoff's

recent awesome San Francisco Performances encore of “Old Man River” to

Chanticleer's new recording of spirituals and traditional gospel music, we

are discovering how music and diversity-embracing activism can transcend

racial division.

The all-male Chanticleer vocal ensemble is hardly all white. For much of its

existence it has benefited immeasurably from the multiple gifts of its

African-American music director Joseph Jennings. Jennings imparts an

authentic spirit to this disc, not least by arranging all the selections,

providing authentic-sounding upright piano accompaniment, and occasionally

offering his voice.

Equal blessing, if I may be so bold, comes from Bishop Yvette A. Flunder (aka

Rev. Dr. Yvette Flunder). From her beginnings singing in her grandfather's

San Francisco church, Flunder transitioned from a solo career to singing and

preaching internationally with the famed Hawkins Family Singers. In 1991 she

founded the City of Refuge Community Church and Ark of Refuge, Inc. in San

Francisco, training African-American church ministries in HIV/AIDS

prevention education and offering housing and support services to people

living with HIV/AIDS. Eight years later, she developed the “One Voice:

Gospel Artists Respond to AIDS” educational campaign and gospel concerts

with the Centers for Disease Control. As Bishop of Fellowship 2000, a group

of 54 churches, Bishop Flunder travels internationally, singing and

preaching a message of inclusivity for all peoples.

What all this talent translates into is an inspiring, musically perfect

disc. Despite frequent personnel changes, Chanticleer remains a crack

ensemble. Thanks to Jennings' direction, every note and word is perfect,

every harmony shining. One cannot help smile when Flunder sings “God” the

way most people in America pronounce it, while the white boys make the word

sound more profound by singing “Gawd,” but they've got the idiom down pat.

Even Philip Wilder's curiously fem soprano solo on “Keep Your Hands on the

Plow,” exclaimed in a voice that sounds more suited to quilt-making than

field work, in the end earns smiles rather than criticism. This is a disc to

banish cynicism.

It is impossible to overstate the brilliance of Joseph Jennings'

arrangements. A recent performance by the East Bay Gay Men's Chorus featured

an arrangement of “We Shall Overcome” that sounded not only repetitively

foursquare – the same off-beat movement between vocal lines in each verse –

but spoiled the sentiment of a civil rights anthem that for years left me in

tears by ending with an overly soppy reprise that seemed best suited to the

vocal equivalent of a Hallmark greeting card.

Jennings makes no such errors. His harmonies, phrasing, rhythms are

constantly alive and changing in ways that enhance rather than distract from

the spiritual message of the music. To cite just two examples out of

hundreds, the traditional “There is a Balm in Gilead” begins with the chorus

offering soft wordless background as Flunder starts her solo. Only when she

begins the recapitulation do the boys begin to sing the words, underscoring

her voice with a softness that sounds like balm indeed. In the subsequent

extended Poor Pilgrim Medley, long-time ensemble member soprano and recent

departee Christopher Fitzsche's very high solo is strikingly followed by

veteran Eric Alatorre's deep bass at the start of “Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow.”

Light and shade, highs and lows, all are judiciously contrasted in perfectly

paced performances filled with spirit.

Spirit and then some also abounds in the Transcendence Gospel Choir's

Whosoever Believes. Based in the Bay Area, the world's only transgender

gospel choir deservedly won the 2004 OutMusic Choral Award for their truly

inspiring disc. The so-so sound of the independent effort cannot compare

with Warner Classics' truthful, state-of-the-art sonics, but the spiritual

conviction is awesome.

The disc begins with Pastor Jonathan Thunderwood and Reverend Dr. Yvette

Flunder preaching a message that reclaims ALL people, regardless of color or

orientation or sexual transformation, as God's children. It's only up from

there, as arrangements by disc producer and alto Ashley Moore and others

find the chorus in inspired form. I don't know how many members of

Chanticleer actually practice Christianity, but it's clear these folks sing

as if their lives depended on it. Perhaps atheists, Martians, those

historically oppressed by Christianity or recovering from church

indoctrination and abuse will go “so what,” but the rest of us will likely

find ourselves on our feet, clapping our hands in praise of a spirit that

ultimately transcends Christianity. The small, one-of-a-kind Transcendence

Gospel Choir (www.tgchoir.org) has created an instant classic, one that

deserves the widest possible audience.

|

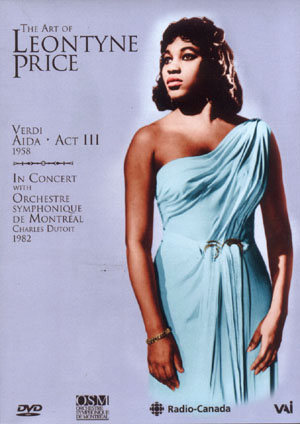

| THE ART OF LEONTYNE PRICE:

RADIO-CANADA TELECASTS, 1958-1982 VAI DVD-VIDEO 4268

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

This historic footage displays the glorious soprano Leontyne Price during

her initial rise to stardom. Complemented by an entire concert performed

live on October 3, 1982 at age 55, less than three years before her

retirement from the operatic stage, the program allows us to assess the

gifts of one of the pre-eminent lirico-spintos of the last fifty years.

Price first assayed her signature role of Aida in 1957, one year before

singing the entire Act III of Aida for this Canadian film. While she had

already toured the U.S. in a production of Porgy and Bess, performed Samuel

Barber's Hermit Songs with the composer at the Smithsonian, appeared in

NBC-TV's 1955 staging of Tosca, sung music by Lou Harrison in Rome, and

created Madame Lindoine in Poulenc's Dialogues of the Carmelites in San

Francisco, audiences were still accustoming themselves to the notion of a

“Negro” cast as a lead opposite whites. Playing Aida, an Ethiopian slave who

falls in love with an Egyptian general, was thus not only an “acceptable”

role for her, but one with which she deeply identified. In few other roles

did Price find a vehicle so perfectly matched to her vocal strengths and

emotional sympathies.

Act III of Aida, staged by Irving Guttman and telecast in black and white on

October 23, 1958, also features Willliam McGrath as Radamès and Napoléon

Bison as Amonasro. Jacques Beaudry conducts L'Orchestre de Radio-Canada. Not

only do we hear her voice in first flowering, but we also see Price act at

age 31, when she was still young, lithe, relatively slender, and less prone

to posturing herself as a goddess. She comes off quite well, exhibiting a

fair amount of dramatic involvement while singing like an angel.

Early in her career, Price's voice was glorious and even throughout the

registers, with those uniquely sensual, thrilling highs of hers spun out

with mesmerizing freedom. Never known for perfect phrasing, she here

exhibits an ease of production, mastery of legato, and technical surety not

always present in later years. While 1982 finds her practicing full out can

belto, in 1958 she allows herself to sing entire phrases softly. She also

exhibits a freedom of tempo and other subtleties often sacrificed for the

sake of being heard at the far end of the hall. The other principals are far

more workaday, with McGrath visually implausible as a war hero. But Price is

truly a soprano to die for.

The 1982 concert, shot in color with Charles Dutoit conducting L'Orchestra

symphonique de Montréal, finds her in drier voice. The opening “Come scoglio”

and “Ernani, involami!” are rough going, Price squeaking out the highest

notes on more than one occasion. The passagio between chest and middle voice

has grown troublesome, with words sometimes half sung/half spoken (even

shouted) to get through the break. But the voice warms up as the concert

continues. Verdi's “Pace, pace mio Dio!” from La Forza Del Destino offers

some breathtakingly beautiful phrases and sounds in the upper middle

register, as well as a thrilling climax. If the voice and temperament are by

this time much too heavy for Puccini's “O mio babbino caro,” Tosca's rapidly

sung “Vissi d'arte” offers tear-inducing beauty.

All important bonus material comes in the form of four snippets from the

Bell Telephone Hour. Leonora's two great arias from Verdi's Il Trovatore

come from 1963, just two years after Price's Met début in the role inspired

one of the longest standing ovations in the house's history. Subtlety of

phrasing learned from Herbert von Karajan remains intact, with the ending of

“D'amor sull'ali rosée to die for. 1966 brings Aida's Ritorna vincitor!,

with Price looking far more beautiful if sounding a shade less inspired than

in 1958. Finally, 1967 gives us a superb “Pace, pace mio Dio,” with the

soprano framed by billowing lavender gauze one month before she hit 40.

|

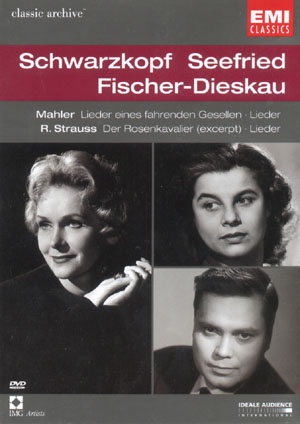

| SCHWARZKOPF SEEFRIED

FISCHER-DIESKAU

EMI CLASSICS DVD 7243 4 90442 9 6

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

This priceless DVD, issued in conjunction with the BBC, offers three of

the greatest singers of the lp era performing the repertoire by Strauss,

Mahler, and Schubert for which they were most prized. Viewing is a necessity

because of the first selection on the program, the Finale from Act One of

Richard Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier filmed in London in 1961 with soprano

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as the Marschallin, mezzo-soprano Hertha Töpper

playing Octavian, and Charles Mackerras conducting the Philharmonia

Orchestra.

Volumes have been written about Schwarzkopf's Marschallin, and for good

reason. Lotte Lehmann, Regine Crespin, and Kiri Te Kanawa all left memorable

interpretations, but only Schwarzkopf's is so vivid and alive to the moment

that she literally seems to transcend Strauss' score and become the

Marschallin.

Schwarzkopf's Marschallin is most remembered from the film and recording of

the famed 1957 production that paired her with Christa Ludwig, Theresa

Stitch-Randall, Otto Edelmann, and conductor Herbert von Karajan. Yet the

soprano has stated on at least one occasion that her interpretation grew in

the years that followed that performance. This footage allows us to see the

difference that four years made.

Though Schwarzkopf was by this time approximately 46 years old, her beauty

and voice had if anything ripened rather than declined. She had also honed

to perfection the Marschallin's every physical and vocal gesture. While her

painstakingly analytical approach to music frequently resulted in

overstated, self-consciously exaggerated lieder performances, it proves

entirely appropriate for the Marschallin's utterly self-conscious

self-critical monologue.

In Schwarzkopf's Marschallin, art and artifice unite as one. Save for two

brief moments when the phrasing seems overdone, her identification with the

character seems utterly natural. Only soprano Magda Olivero's verismo

interpretations from the same period achieve Schwarzkopf's level of

veracity. Hertha Töpper may be a vocally non-ingratiating Octavian, but her

square-jawed countenance adds a touch of credibility to the pants role.

Next on the program, soprano Irmgard Seefried, one of Schwarzkopf's greatest

rivals in lieder interpretation, sings five lied by Strauss in Salle Pleyel,

Paris in 1965 and three songs by Mahler at the ORTF, Paris in 1967. Although

she was known for her simple purity of voice and interpretation, Seefried

seems either past her prime or in less than ideal voice or both. With no

help from frequently distorted sound, the footage fails to satisfy.

The DVD ends with two major contributions from Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.

Blessed with a gorgeous voice, the baritone shared with Schwarzkopf the

tendency to concentrate on the minutia of lieder interpretation. Happily,

these performances are from a less mannered period early in his career, when

he was also in most beautiful voice. Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden

Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer), with the NHK Symphony Orchestra under Paul

Kletzki, comes from Salle Pleyel in 1960, followed by four Schubert lieder

accompanied by Gerald Moore in London in 1959. The value here is in the

singing rather than the visuals.

|

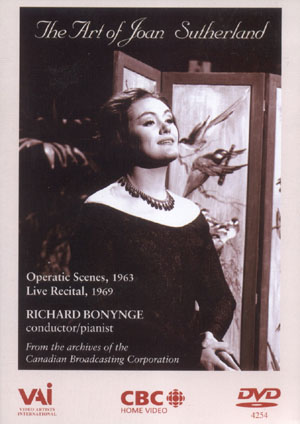

| THE ART OF JOAN SUTHERLAND RICHARD BONYNGE, CONDUCTOR/PIANIST

VAI 4254

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

From the archives of the Canadian Broadcast Corporation come two previously

unreleased programs featuring coloratura soprano Joan Sutherland (not yet

Dame Joan) expertly supported by her husband Richard Bonynge. The first,

filmed in black & white in 1963 expressly for the CBC, intersperses

Sutherland's stilted, formal spoken introductions to the lives of great

coloraturas of the past (complete with deadening stills of portraits and

interminable panning of walls) with brilliant performances of arias either

written for or closely associated with those sopranos. Accompanied by the

CBC Orchestra conducted by Bonynge, and joined in duet by slight-voiced

tenor Richard Conrad (who also contributes a solo from Donizetti's Don

Pasquale). Sutherland sings two arias from Bellini's I Puritani, “Bel raggio”

from Rossini's Semiramide, coloratura displays by Benedict and Ricci, and

Violetta's first act scena from Verdi's La Traviata. The upper range is

brilliant, the coloratura leaps, trills, and runs stunning. Though she was

hardly an insightful interpreter, Sutherland as technically astounding

vocalist was at this point in her career beyond compare.

From six years later, Sutherland presents a live, performed-for-television

recital filmed before an initially enthusiastic audience. With Bonynge

playing the piano wonderfully while maintaining an absolutely unmoving

visage in order to maintain all focus on his prima donna, Sutherland mainly

performs works that lie lower in her range. Only occasionally displaying her

brilliant top and coloratura mastery, she delivers mostly dreary renditions

of works by Gretchaninoff, Rossini, Bellini, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet,

Delibes, Bononcini, Handel, and Alabiev. Poor enunciation, unvaried tone and

lack of emotional expression do not great singing make.

The most interest comes when she fluffs the opening line of one selection,

leans over the piano toward Bonynge and begins cursing her gown off. She

catches herself in the middle of “shhhhh…” After getting a good laugh out

and regaining her composure, she starts over, this time with every note

perfectly in place. Even Balfe's “I dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls,” a piece

dear to her heart learned from her mother, proves prosaic. But the

coloratura from 1963, and the opportunity to see La Stupenda briefly let her

hair down are to treasure.

- Jason Victor Serinus

-

Terms and Conditions of Use

|