For a few words about my

reviewing process and preferences, please see the introduction to

Classical Review #36.

|

| MAHLER: SYMPHONY NO.

4 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON

THOMAS, COND.

SFS MEDIA 0004

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Right before Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony performed

Gustav Mahler's Fifth Symphony in Boston and New York, their Delos SFS Media

label released their live recording of Mahler's happiest symphony, Symphony

No. 4. The fourth offering in the San Francisco Symphony's ongoing Mahler

series, the single CD offers glorious sound and musicianship and the option

of superior SACD surround sound playback.

Mahler marked his first movement “Deliberately. Do not hurry.” Tilson Thomas

takes this indication (as well as all of Mahler's subsequent instructions)

seriously. The opening is quite laid back; whenever the tempo quickens

momentarily, the orchestra soon returns to a leisurely pace. The conductor

gives us ample time to savor Mahler's sleigh bells, his quasi-chamber music

ride on a sunny day. San Francisco's players luxuriate in the music's

textures, the winds especially fine. Even when the music becomes

increasingly clouded, threatening to break into yet another outpouring of

Mahler's perpetual angst, it suddenly stops in its tracks; after telling

silence, the sleigh ride continues as if nothing had happened. While Tilson

Thomas savors the movement's conclusion, building it to a rousing climax,

his generally understated interpretation may fail to fully engage listeners

partial to the bite and variety of George Szell's classic rendition.

Gustav's wife Alma Mahler (a composer in her own right until hubby put a

stop to her music writing) said of the second movement, “The composer was

under the spell of the self-portrait by Arnold Böcklin, in which Death

fiddles into the painter's ear while the latter sits entranced.” MTT's is a

very playful Death, one who toys with termination rather than pulling the

plug. This Totentanz becomes a waltz --“In easy motion. Without haste” wrote

Mahler -- as Death seems to dance out of view, allowing us to savor the

sweetness a bit longer. The playing is exemplary.

MTT's start to the great third movement Adagio (“Peacefully') is so

heartfelt and warm it makes you want to cry. San Francisco's violins

superbly maintain a long, sustained high note that seems to stretch into

infinity before gently descending from the heights. Even when the music

becomes mournful, then tragic, Tilson Thomas gently reconnects us to the

symphony's overriding sweetness. The end unfolds as a glorious sonic

spectacle, triangle and timpani resounding as heaven's gates open to welcome

us.

The “very leisurely” fourth movement is a soprano setting of a Bavarian folk

song from the Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth's Magic Horn) poetry

collection that so influenced the development of Mahler's first four

symphonies. The music to the song, “Heaven is Hung with Violins,” was first

sketched in 1892, seven years before Mahler began to compose the rest of the

symphony. As such, this final movement must be understood as the raison

d'etre -- “the tapering Pinnacle” as Mahler told a friend -- of the symphony

as a whole.

The orchestra segues seamlessly into Mahler's heavenly dimension. Mahler

specifically requested “a singing voice with a gay, childlike sound, but

entirely free from parody” for this child's description of an unquestionably

glutinous, meat-laden heavenly paradise.

Though high-flying soprano Laura Claycomb provides requisite sweetness, her

singing cannot compare with Lorin Maazel's Kathleen Battle (ideally innocent

and small, yet filled with wonder and rapt expression) and George Szell's

Judith Raskin (mature sounding at first, but miraculously transcendent and

radiant as she sings “There is no music on earth that can be compared to

ours… The angelic voices gladden our senses, so that everything awakes to

pleasure”).

In part this is the conductor's responsibility; the magical slowdown of the

start of the final verse heard in many versions, or the orchestral

punctuations between verses that in Bernstein's hands (with the New York

Philharmonic) sound like a child pouting, are here absent. San Francisco's

horns drolly underscore St. Luke's slaughter of the ox, making them sound

drunk with wine, but the violins virtually overlook the fish gladly swimming

along. Tilson Thomas laudably never upstages his soloist (here far more

audible than in live performance) by spotlighting Mahler's orchestral

commentary, but neither does he succeed in drawing from her the ultimate and

indispensable heaven-sent statement.

Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony have just launched a

five year multi-media project designed to “change the climate of national

opinion regarding classical music and to make the music more accessible and

enjoyable to a wider range of audiences. Look for their late spring two-part

PBS Great Performances exploration of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 4 featuring

MTT and the SFS.

|

| FDEL TREDICI: VINTAGE

ALICE SYZYGY * JOYCE SONGS

LUCY SHELTON, SOPRANO; DAVID DEL TREDICI, PIANO;

ASKO ENSEMBLE

OLIVER KNUSSEN, COND.

DG 447 753-2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Until this exceptional release, the great David Del Tredici hadn't seen a

release of his music since 2001's Secret Music issue on the lamentably

departed CRI label (currently available for $3.99 plus shipping from

qualiton.com). Del Tredici is thus delighted at the unexpected issue of his

1972 Vintage Alice, “A Fantascene on “A Mad Tea-Party” from Louis Carroll's

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and other Victorian materials.” Paired with

earlier songs to poetry by James Joyce, the music appears as part of DG's

prestigious 20/21 series.

Recorded between 1993 and 1997, the performances finally reach the light of

day thanks to conductor Oliver Knussen, who exercised an option on his DG

contract to share Del Tredici's music with a wider audience. Soprano Lucy

Shelton, a high-flying modern music specialist who was dating Knussen at the

time, joins Knussen conducting the Asko Ensemble plus Del Tredici on piano..

Vintage Alice is one of many Alice settings from the 67-year old Del Tredici.

David won the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for In Memory of a Summer Day, extracted

from his brilliant longer work, Child Alice. His other Alice pieces include

An Alice Symphony (1969), Final Alice (1974-75) for amplified soprano, folk

group and orchestra, and Haddocks' Eyes (1985) for amplified soprano and ten

instruments. All reflect Del Tredici's ongoing fascination with Carroll's

fantasy.

Speaking from his New York City home via a device absent from Carroll's

universe, Del Tredici expressed his pleasure with DG's “beautiful

production. I haven't had a European disc in awhile, and it has already

gotten some quite good reviews in Time Out New York and Gramophone. I'm very

pleased.”

Since I had reviewed the San Francisco Symphony debut of Del Tredici's Gay

Life for Opera News, conversation naturally turned to that work. The

symphonic cycle for baritone and orchestra to texts by Paul Monette, Allen

Ginsberg and others was commissioned by San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and premiered in 2001 to a mixed reception

from audience and critics alike/

Gay Life's cool reception hardly equaled the censorship that greeted the

aborted June 21, 2003 Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival debut of Del

Tredici's Wondrous the Merge. The 20-minute string quartet, written for the

Elements String Quartet, was to include James Broughton's explicitly erotic

poem of the same name in mostly spoken form. Because the spoken text was

deemed too risqué for Michigan, only the non-controversial baritone aria

plus its instrumental music was performed.

Shortly before the performance, Del Tredici learned that the Festival is

funded by a Catholic Church, a Jewish Synagogue, and a Protestant Church.

“That seems to me to be the problem. They told me that the poem's language

was too sexually explicit for their audience. For an older,

pillar-of-the-community married man like Broughton to realize and act upon

his long-repressed homosexuality, as his autobiographical poem depicts, is

the right wing's worst nightmare.”

Del Tredici refused to allow the Festival to call the performance a world

premiere. Nor did he attend as planned. The full premiere will take place in

New York's prestigious Merkin Hall this fall.

Vintage Alice is much less controversial in its subject matter. Its fabulous

music is distinguished by Del Tredici's hilarious inventiveness and

fantastic leaps of musical imagination. Yet it too caused controversy,

because it was one of the first tonal works the born again neo-romanticist

dared to offer a musical establishment that considered the tonality of the

three Bs passé.

“I discovered Lewis Carroll's sentiment, his world of wit and whimsy

demanded another kind of music. Without realizing it, I got tonal.”

While Del Tredici acknowledges that wit and whimsy had always been a part of

him, he had never before considered putting it into his music -- the earlier

songs on the disc are seriously atonal, albeit gorgeous and compelling --

until he discovered in Alice “a way to let out my humor into music. I saw

things in the text that I wouldn't have thought of had I not had that text

in front of me.” Listeners will especially enjoy the rhythmic distortions

that accompany the Queen's declaration, “She's murdering the time.”

Forthcoming Del Tredici débuts include the April premiere of My Goldberg

with pianist Bruce Levingston in Alice Tully Hall. (Three Gymnopédies

written for Levingston may be performed at the new opening of MOMA). Gotham

Glory: Four Scenes from New York, a commission from Carnegie Hall written

for pianist Anthony De Mare, receives its premiere in Zankel Hall in March

'05. Fantasy on “Nobody Knows” recently received a world premiere in upstate

New York, and the must-hear Dracula (1996-1998), performed at last summer's

West Coast Cabrillo Music Festival by the fabulous soprano Hila Plitmann and

conductor Marin Alsop (and reviewed by moi for Opera News), just attacked

Denver. Add in Kalamazoo, Dallas, Fort Worth, Toronto, and Waco and you're

up-to-date until Del Tredici strikes again.

|

| CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS:

THE CARNIVAL OF THE ANIMALS * SEPTET RENAUD

AND GAUTIER CAPUÇON, EMMANUEL PAHUD, PAUL MEYER, ETC

VIRGIN CLASSICS 7243 5 45603 2 3

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

It is hard to believe that Camille Saint-Saëns actually forbade public

performance of his “Grand Zoological Fantasy” Le Carnival des Animaux during

his lifetime. Only the much-loved “Le Cygne” (“The Swan”), one of the work's

fourteen musical portraits of the animal kingdom, was allowed public airing.

If “The Swan” has remained the most popular of the Carnival's fantastic

portraits – it has been performed on every instrument imaginable including

the early electronic theremin -- it is not because the other inhabitants of

Saint-Saëns' zoo are less deserving of attention. The whole work, especially

as heard here in its original chamber ensemble arrangement for eleven

instruments including harmonica and xylophone, is a kick and a half.

The work begins with the Royal March of the Lion, then goes on to describe

chickens and cocks, tortoises, an elephant, kangaroos, an aquarium, a

cuckoo, and such untamable beasts as wild asses and pianists. The latter

section contains elements of self-parody, the composer having first come to

public attention as a 10-year old piano prodigy who matured to make part of

his living as a virtuoso organist. (Liszt called him the greatest organist

in the world). The music varies from the magical (the bubbling water of the

aquarium and the graceful lines of the swan) to the hilarious (including

lumbering elephants, braying asses, and the final assault of the menagerie).

Each portrait is unveiled with a fresh sense of wonder. The ensemble

dominated by the Capuçon team of violinist Renaud and his cellist brother

Gautier and seconded by pianists Frank Braley and Michel Dalberto, plays

superbly. The musicians launch into Saint-Saëns' music with great vigor.

Pulling out all the stops, they have riotous fun with the Carnival's

excesses, while quite subtly conveying its delicate moments.

The players are equally spirited in the last work on the disc, the

wonderfully lighthearted Septet. In between, we hear three charming works.

Far more substantial than most salon fare, they include a fantasie for

violin and harp and two pieces for cello and piano. Gautier Capuçon and

Frank Braley also perform Georges Papin's transcription of Saint-Saëns'

great aria from Samson et Dalila, “Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix.”

Saint-Saëns' music is often subject to disparagement. Such was also the case

with the oeuvre such composers as Piotr Tchaikovsky and Reynaldo Hahn until

their recent championship by conductors Michael Tilson Thomas and Valery

Gergiev (Tchaikovsky) and mezzo-soprano Susan Graham (Hahn) revealed anew

their great gifts. Anyone listening to this disc will discover a newfound

appreciation for the beauty Saint-Saëns could create on a good day.

|

| AROSA PASSOS & RON

CARTER: ENTRE AMIGOS/AMONG FRIENDS CHESKY

RECORDS JD247

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Brazilian vocalist and guitarist Rosa Passos made a huge impact on the

American public when she appeared on one track of cellist Yo-Yo Ma's

Grammy-winning crossover excursion into Brazilian music, Obrigado Brazil.

Her cool, understated singing, with its seductively soft intensity and

soul-breathed edge seemed perfect for the two tracks by Antonio Carlos Jobim

heard on that disc. It is therefore a delight to discover this superb artist

lending her voice to all eleven tracks of this superbly recorded CD from

audiophile label/jazz specialist Chesky.

Passos is in fine company, joined by no less a jazz luminary than bassist

Ron Carter. With Lula performing the guitar solos, Palo Braga on assortment

of cleanly recorded, remarkably lifelike percussion, and Billy Drewes on

tenor sax and clarinet, we are treated to musicianship of the highest order.

These musicians' reinterpretation of Jobim & De Moraes' “Garota de Ipanema”

(“The Girl from Ipanema”) must be heard. Personally, I have savored it over

and over.

Seven of the tracks are by Jobim, with others by Noel Rosa, Bide & Marcal,

Garota & Luis Claudio, and Dennis Brian. The music is consistently

seductive, communicating the warmth of the Brazilian rainforest and the

mystery of the country's strong spiritualist tradition. Though lamentably

lacking translations, the Portuguese texts' emotional essence, wedded to

music sometimes cool yet paradoxically warm to the touch, speaks louder than

words. Besides, Passos is so remarkable that to our ears, she might sound

equally compelling singing a page of entries from the Buenos Aires Yellow

Pages. (Sony has just signed her to an exclusive contract).

Chesky's sound is all one might wish for. In some of their earlier releases,

the company concentrated on “audiophile effects” that would make different

instruments seem to emanate from different corners of the room. It was a

trip, but it did not reflect the realities of live performance. This

presentation is far more honest and less souped up, with bass on the left,

voice toward but not exactly in the middle, and other instruments to the

right. Space between them is large and engrossing. Highly recommended on all

counts. I now use this disc when I test equipment because it's so enjoyable

and well recorded.

|

| YO-YO MA

OBRIGADO BRAZIL LIVE IN CONCERT

SONY 90970

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

A huge nod to this live recording of cellist Yo-Yo Ma's latest world

music excursion. America's great musical ambassador, who has previously

brought us the music from the Silk Road, France, the Appalachias, and the

classical masters here joins Brazilian vocalist/guitarist Rosa Passos,

joyful Cuban clarinetist Paquito D'Rivera, guitarist/composers Sérgio &

Odair Assad, pianist Kathryn Stott, bassist Nilson Matta, and percussionist

Cyro Baptista for over 72 minutes of music and audience appreciation from

Carnegie Hall's new Zankel Hall. The sound isn't as rich as on the

Grammy-winning studio venture of the same name (previously reviewed), but

neither are Passos' voice or any of the other instruments over-hyped with

extra reverb. Instead we've got the real thing: gorgeous, spontaneous, and

generous in its musicianship.

Passos, who has just signed an exclusive contract with Sony, appears four

times. In addition to much music by Jobim, two cuts by D'Rivera, and

assorted tracks by Gismonti, Sérgio Assad and others, we're treated to three

reinterpretations of the music of the great Astor Piazzolla (classically

trained by Nadia Boulanger in Paris before she sent him back home to write

the tango music that was in his blood).

The repertoire on this disc is perhaps more suited to a crossover audience

than on the original issue (which nonetheless won the Grammy for crossover).

Despite its overriding sense of joy and celebration, I miss the studio

disc's two tracks by the great Brazilian classical composer Heitor

Villa-Lobos, as well as another by Pixinguinha. But given the quality of the

substitutions, both discs are recommended.

Brazilian music has a sound all its own, one that affirms the vast beauty

and mystery of our multi-colored universe. For opening our eyes and

enlarging our vocabulary, it deserves a section all its own on your shelf.

|

| The Gift To Be Free:

Songs by Aaron Copland Susan Chilcott,

soprano; Iain Burnside, piano

BBC Black Box BBM1074

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

The same year that Aaron Copland wrote his great American song cycle,

Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson, the FBI opened a Copland file. Three years

later, the Jewish-American composer of such quintessentially American music

as Lincoln Portrait, Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, and the Fanfare for the

Common Man (former campaign theme music for the Republican Party) was

dodging questions about his commie-pinko proclivities from Senator Joseph

McCarthy, whose House Un-American Activities Committee served as a warm-up

for John Ashcroft's terrorist under every tree Patriot Act.

Highest accolades go to soprano Susan Chilcott and pianist Iain Burnside for

this superb recital (with extra kudos to Burnside for discussing Copland's

identity in the excellent liner notes). Just as the great British contralto

Kathleen Ferrier made some of her most moving recordings fifty years ago

while fighting the leukemia that would shortly claim her life, Chilcott

recorded these songs while coming to terms with the cancer that killed her

last year at the age of 40. Chilcott and Burnside deliver performances of

great immediacy, highly spirited in the more extroverted songs, deeply

moving when expressing inward sentiments. Though Copland chooses not to

stretch his songs out to the romantic lengths that Mahler reached in Das

Lied von der Erde, his less pretentious statements evoke an America true to

our collective experience.

The recital begins with the first set of Old American Songs that Copland

penned in 1950. The romanticized masculinity of the rousing “The boatmen's

dance” paves the way for the composer's sly condemnation of politician's

lies, “The dodger (Campaign song).” Then, the much loved “Long time ago” and

traditional Shaker song “Simple gifts,” both arranged with understated

artfulness, lead to “I bought me a cat,” a delightful secular Children's

song with parallels to “The Twelve Day of Christmas.” Chilcott may be

English by birth, but besides a very occasional lapse into proper British

vowels detectable only to the extra-attentive, her renditions are as

idiomatic as they come.

Then we move into the deep stuff, Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson. Although

Copland did not have access to less sanitized versions of poetry from the

recluse of Amherst -- versions that only received first publication after

Copland wrote his songs -- his creations are filled with passion that cries

out to us. Chilcott's “I felt a funeral in my brain,” “Going to Heaven!” and

“The chariot” (“Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for

me”) convey a poignancy all the more palpable for her health challenges.

Three early Copland songs include “Night” (1918) from his student days and

the rare atonal “Poet's Song” (1927) set to text by E.E. Cummings. As is the

case with Chilcott's “Heart, we will forget him” from the Dickinson set, her

collaboration with Burnside on the beautiful “Pastorelle” (1921) focuses

less on the gentle, heartfelt repose one feels from the duo of soprano

Arleen Auger and Dalton Baldwin than on Copland's dissonant commentary. As

much as I wish for a steadier opening to “Pastorelle,” the added insight

afforded by these tangy performances leaves me feeling like I have heard the

songs anew.

Four Piano Blues for solo piano pave the way for Copland's second set of Old

American Songs. “The little horses,” “Zion's Walls,” “At the river” and

“Ching-a-ring chaw” have become classics, as American as Debussy's “Clair de

lune” is French or Brahms' “Von ewiger Liebe” is German. Some may prefer a

naïve, apple pie voice, but the pain one feels when Chilcott sings “Hush you

bye, don't you cry” or “Shall we gather by the river, Where bright angels

feets have trod” elevates her singing to another dimension. This is a superb

recital.

|

| THE ART OF LJUBA

WELITSCH PREISER 90476 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| KARAJAN EDITION:

GERMAN OPERA EMI 7243 5 66394 2 3

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| SALOME: RICHARD

STRAUSS WIENER PHILHARMONIKER, HERBERT VON

KARAJAN

EMI 72432 5 7152 2 9 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| SALOME: RICHARD

STRAUSS WIENER PHILHARMONIKER, SIR GEORG SOLTI

LONDON/DECCA 414 414-2 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| SALOME: RICHARD

STRAUSS ORCHESTER DER DEUTSCHEN OPER BERLIN,

GIUSEPPE SINOPOLI

DG 431 810-2 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

| SALOME: RICHARD

STRAUSS VIENNA STATE OPERA, KARL BÖHM

OPERA D'ORO OPD 7004 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

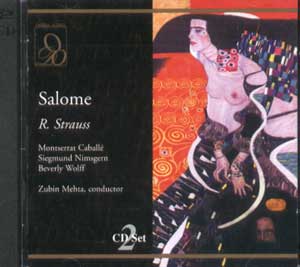

| SALOME: RICHARD

STRAUSS RAI ORCHESTRA & CHORUS, ZUBIN MEHTA

OPD-1311 (2 CD)

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

A GUIDE TO RICHARD STRAUSS' SALOME ON DISC

With soprano Karita Mattila currently assaying Strauss' Salome at the Met

for the first time, and her astounding singing and acting earning even more

attention than her strip-tease, it is time to revisit the great recordings

of this one-act operatic masterpiece.

Oscar Wilde's play Salome, written in French in the winter of 1891-2, so

influenced Richard Strauss when he saw it in German translation in Berlin in

1902 that he chose it as the subject of his third opera. Ever since the

opera's premiere in Dresden on December 9, 1905, lyric/dramatic sopranos

have been screaming their lungs out to Strauss' score, frequently if

unintentionally massacring their pseudo strip tease before unleashing their

venom on the summarily decapitated John the Baptist.

On opening night, Strauss' audience demanded 38 curtain calls. The Church

was not amused. Neither was the Metropolitan Opera; its 1907 premiere

generated critical wrath and donor disdain, with the daughter of capitalist

financier/slave baron J. Pierpont Morgan interceding to cancel further

stagings.

At their most extreme, critics and censors demanded that Strauss' head

rather than John the Baptist's be severed and paraded before audiences. When

Sir Thomas Beecham conducted the Covent Garden premiere in 1910, the text

was heavily censored and Salome was forbidden to carry anything suggesting

John's head on her platter. Austria's Salzburg Festival waited until 1929 to

semi-officially mount a single performance conducted by a precocious 21-year

old Herbert von Karajan. Only in 1977 was Karajan again invited to stage and

conduct the work in the famed music capital.

Today, Salome is treasured as a glorious one-acter that mixes shocking

tonalities with some of the most unabashedly sensual music ever written. But

only when this tour de force enlists musicians of the highest caliber does

it succeed in thrilling us to the core.

The most famous Salome on records, the Bulgarian Ljuba Welitsch, was 31 when

she coached the role in 1944 under an 80-year old Strauss. Her first

recording of Salome's extended final scene, made that same year, reveals a

remarkably even, youthful and silvery voice tainted by an innately obscene,

ideally crazed quality. This 1944 performance seems unavailable in the US

other than on the old, inferior sounding EMI References Welitsch: Salome;

Welitsch's later complete Met broadcast under Reiner, only available in the

US from the Met, costs a goodly sum.

Happily, there are to alternatives. EMI Classics' Karajan Edition includes

Welitsch's stunning 1948 performance of most of the final scene, while

Preiser's invaluable two-disc The Art Of Ljuba Welitsch offers a slightly

less unhinged 1950 studio recording with Reiner. Both are must-hears, with

my vote going to Karajan.

Four years at the Met and countless beheadings wrecked Welitsch's voice

within 10 years. Not until Leonie Rysanek's 1971 traversal of the role under

Böhm, preserved in a well-mastered 1972 live recording on Opera D'Oro Grand

Tier, and Hildegard Behrens' 1977 portrayal with Karajan and the Vienna

Philharmonic on EMI do we again experience such riveting intensity on disc.

Rysanek is spectacular. The voice possesses awesome force and beauty, her

sincerity of utterance distinguished by high notes hurled out in luminous,

life-depends-on-it fashion. Böhm's orchestra, albeit deprived of ideal

miking, remains right with his singers, never upstaging their efforts. The

veteran Strauss conductor's Dance of the Seven Veils is one of the finest on

records, simultaneously sensual and lush, with a fast-paced, frantic ending.

Behrens, on the other hand, is totally out there. Her Salome is certifiably

nutso, hysterical beyond belief. Though neither she nor Rysanek sound young,

Behrens' voice soars in the romantic passages like a virgin on steroids.

Elsewhere she tears the veils off the role, screaming, shouting and singing

with whatever shreds of a mind seem left to her. Karl-Walter Böhm's Herod

and Agnes Baltsa's Herodias are equally out of bounds.

Karajan is the only conductor who seems capable of coaxing his orchestral

players to first undress and then descend into utter madness. After the

Dance of the Seven Veils' frantic opening, its pace slowly dramatically,

Vienna's winds and strings incomparably sensual and silky. The climax, where

Salome drops her seventh and final veil, segues from expected cacophony to

widely spaced, thunderous drum thwacks that reinforce the soprano's depraved

derobing. Here is a lifetime of Strauss conducting honed to its finest

expression.

Wagnerian soprano Birgit Nilsson's remastered London/Decca set with Georg

Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic has often been lauded as “the” set to own.

Though Nilsson need not exert undue effort to be heard above a huge

orchestra blasting away, her Salome seems underplayed. Certainly she is in

stunning and most fluid voice, with Solti whipping it up like nobody's

business, but all the noise in the world can't compensate for a lead who

seems to strip with leg warmers still on. The whole thing leaves me cold.

The much-lamented Giuseppe Sinopoli was one of our finest Strauss

conductors; his 1990 DG traversal with the Orchester der Deutschen Oper

Berlin is well recorded and fascinating. Rysanek, now 64, returns as an

ideally aged Herodias, and Bryn Terfel is a great John the Baptist. The

question mark involves Cheryl Studer's Salome. Her fragile beauty above the

stave reminds us that Strauss begged the slender-voiced, silvery soprano

Elisabeth Schumann, whose unequalled mixture of charm and spiritual

conviction made her an unlikely candidate for the role, to play Salome.

Though Strauss promised to rescore the work for her, thinning out the

orchestration, Schumann wisely declined, instead choosing to tour the United

States in song recital with Strauss at the piano. Studer works hard, but the

voice seems neither sufficiently big nor demented enough for the Salome of

our nightmares.

The astounding Montserrat Caballé, though physically unsuited for the role,

recorded it for RCA (deleted) and performed it live with Zubin Mehta and the

RAI Orchestra in 1971. Allegro's sound is unforgivably filtered, but Caballé

triumphs nonetheless. She alternately shouts and screams, takes Callas-like

risks with the chest voice, and purrs out shimmering pianissimos like no

other diva known. The transfer to CD is so bad that I can't tell what Mehta

is doing. Regardless, hearing this amazing portrayal reminds us that vocal

greatness, even in the darkest and most decadent of contexts, is itself a

spiritual act capable of illuminating humanity's shadow side with

transcendent force and beauty.

- Jason Victor Serinus

-