For a few words about my

reviewing process and preferences, please see the introduction to

Music Reviews No. 36.

Introducing Il'ya Murometz,

“complete and uncut,” just as Reinhold Glière (1875-1956) wished you to

hear his symphony about the mythical marvel named Murometz. Behold 72

minutes of seductive bombast about an innocent Russian superhero of

enormous physical strength who fought evil, defended the simple folk,

spoke up to authority, and first waved his sword a good 1000 years before

Clark Kent shed his garb in a phone booth. If in the end his musical

representation doesn't have much substance, it nonetheless showcases him

so spectacularly attired in Telarc high-resolution sound that even the

most jaded will find themselves seduced by the glitz.

Glière, who publicly tutored students as professor at

the Moscow Conservatory while privately teaching the young Sergei

Prokoviev, was anything but a musical revolutionary. Considered the bearer

of the classical tradition both before and after the Communist revolution,

his nationalistic works were praised and studied in the USSR as examples

of a successful union between Eastern folklore and central European form.

In no danger of condemnation by Stalin, he was a member of many official

committees and was lauded as a People's Artist of the USSR. If his

well-know ballets such as The Red Poppy

(1927) and Taras Bulba

(1952), and his oft-played

“Hymn for the Great City” excerpted from his ballet The Bronze

Horseman (1949), and his numerous

works in other mediums in the end fail to reveal an individual voice, they

nonetheless contain enough rousing music to provide a classical evening's

alternative to the formulaic melodies of Madonna, Britney Spears and crew.

Il'ya Murometz was written between

1909 and 1911. An attempt to create a picturesque nationalistic epic, its

programmatic content seems more than coincidentally reminiscent of the

Romantic tone poems of Richard Strauss with a little Wagner, Borodin, and

Glazunov thrown in. The first movement, entitled “Wandering Pilgrims:

Il'ya Murometz and Svyaatogor,” introduces our hero. The son of a peasant,

Il'ya spends his first thirty years immobile, warming himself atop a

household stove until two ancient holy men get him off his tail by

predicting that he will become a powerful knight errant (bogatyr). When

Il'ya inherits the knight errant Svyatogor's powers, he mounts his mighty

steed, leaping over rivers and lakes. As his horse's tail sweeps away

whole cities as it passes, the music builds to

climaxes impressive enough to replace

ennui with wonder.

The 20-minute second movement andante, “Il'ya

Murometz and Solovei the Brigand,” offers much beauty with its orchestral

birdcalls (no Messaien dissonance here), mock animal cries, and sensual

portrayal of Murometz's seduction by the daughters of the supernatural

Solovei. If these gals can't build up the erotic charge of Strauss'

Salome, and the music's exoticism can't touch that of the French

impressionists, this movement nonetheless contains much undeniable beauty.

Unless your ancient Russian blood has already been

set aboil, you probably don't give a damn about the stories that inspire

Glière's third and fourth movements. Suffice it to say that the third

offers lots of wondrous excitement, while the tremendous triumph

communicated in the fourth's portrayal of Murometz's heroic deeds will

shake the rafters and drive evil spirits from your door. You may not

remember any of the tunes, but you'll undoubtedly mutter “wow” as you move

on to the ten o'clock news. This disc sounds fabulous in a good

two-channel set-up; in superior SACD format, and especially in surround

sound, it should provide a satisfying sonic alternative to another home

theater evening of gut-shaking brutality and gratuitous violence.

|

|

|

Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth's Magic Horn)

Bonney, Goerne

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Chailly

Decca 2894673482

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Having recently interviewed baritone Matthias Goerne

in conjunction with his April Boston Symphony Orchestra performance of

eight songs from Gustav Mahler's Des Knaben Wunderhorn

orchestral song cycle [see the

Secrets archives], it is most

gratifying to discover him delivering Mahler with the same mesmerizing

sensitivity and vocal beauty that he brought to his recent recording of

Franz Schubert's Die schöne Müllerin.

And while the baritone's extremely slow tempi for some of the Schubert

songs have wowed some critics while dismaying others, few will question

that his Mahler interpretations are well nigh ideal.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

was originally the title of a large

collaborative collection of poems written in German folk style by Achim

von Arnim and Clemens Brentano. Published in 1805 and 1808, the poems

first came to Mahler's attention in the early or mid 1880's, when he was

in his early or mid twenties. From 1888 to 1902, he wrote no less than

two-and-a-half volumes of songs inspired by the collection. So important

were the Wunderhorn poems

to his output that the song “Urlicht” (Primeval Light) became the fourth

movement of his Symphony No. 2, “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” (St.

Anthony of Padua Preaches to the Fish” served as the basis of its third

movement scherzo, and “Das himmlische Leben” (The Heavenly Life) became

the final movement of his Symphony No. 4.

According to Goerne, some of the Wunderhorn

songs were an attempt on Mahler's part to criticize the growing militarism

in Europe. Unfortunately, the baritone asserts, “Mahler's creation was not

strong enough. It was impossible in this period to make the kind of

anti-war criticism in music that was later possible for Berg, Schoenberg,

Eisler, Weill and Brecht… The words are incredible, but in the end, the

climax of the harmonies is so strong that everyone forgets what you are

telling them. The settings are so beautiful musically that they kill the

effect of the texts.”

Be that as it may, few vocal lovers will miss the

bite of the line “I can and will not be merry!” with which baritone and

orchestra launch the opening “Der Schildwache Nachtlied” (The Sentinel's

Night Song). Here, as in many of the Wunderhorn

songs based on a poetic dialogue between “He” and “She,” Goerne sings both

parts, balancing the manly thrust of “his” martial tone with a gorgeous

softening on “her” final sustained high note.

Soprano Barbara Bonney sings the jolly second song,

“Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht?” (Who made up this ditty?) plus four

others. The choice of a soprano rather than mezzo to sing all but one of

the songs here assigned to female voice is certainly valid – soprano Lucia

Popp sings on recordings by Bernstein (his digital remake) and Tennstedt,

and Jessye Norman does the honors for Haitink -- but the energy Bonney

brings to the cycle is less satisfying than that of lustrous mezzo Christa

Ludwig (Bernstein) or Anne Sophie von Otter (Abbado).

Bonney certainly knows how to negotiate her low

notes, and to lighten her voice to lovely effect on mids and highs.

Marvelous in “Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” (When the shining trumpets

are blasting), which she sings raptly with moving subtlety and care, she

just misses the mark elsewhere. A case in point is the glorious extended

vocal movement that concludes Mahler's Fourth Symphony. Bonney's

interpretation of this child's view of heavenly paradise swings between

welcome naïve sweetness and inappropriate maturity, as though she isn't

exactly sure of whom she is. (Listen to the young Kathleen Battle for an

ideal performance of this movement). There's certainly much to admire, but

far less to cherish.

No such case with Goerne. The man is brilliant. With

a voice alternately virile and achingly tender, he gifts Mahler's creation

with the steady flow of beauty it deserves. Chailly provides fine,

transparent accompaniment, and mezzo Sara Fulgoni and tenor Gosta Winbergh

do well with the one song each assigned to them. But ultimately it's

Goerne's show, and Mahler is all the better for it.

|

|

|

David Diamond: Symphony No. 1, Violin Concerto

No. 2, and The Enormous Room

Fantasia for Orchestra

Seattle

Symphony, Gerard Schwarz

Naxos 8.559157

David Diamond: Psalm,

Kaddish for Cello and

Orchestra (1987), Symphony No. 3

Seattle

Symphony, Gerard Schwarz

Naxos 8.559157

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

SPOTLIGHT ON DAVID DIAMOND

One of the more prolific American composers of the

last century, David Diamond turned 88 on July 9. Although he has never

achieved the mass popularity and acceptance of such well-known 20th

century American compatriots as Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, and Leonard

Bernstein he has created an impressive body of finely crafted work whose

tuneful romanticism and ruminative feel continue to win converts.

Bargain label Naxos has recently released two discs

of Diamond's orchestral works as part of their indispensable American

Classics series; another two discs are forthcoming. All are reissues of

Seattle Symphony performances recorded for Delos in the early 1990s, and

the Seattle Symphony conducted by long-time Diamond champion Gerard

Schwarz.

Diamond's association with the Seattle Symphony dates

back almost 30 years; he remains their Honorary Composer in Residence.

While new liner notes have been prepared for Naxos, they include quotes

from interviews with Diamond printed in full in the original Delos

brochures.

The first disc (Naxos 8.559155) features two “ritual”

works, Psalm (1936) and

Kaddish for Cello and Orchestra

(1987), plus Symphony No. 3 (1945). Psalm

was first performed in 1936 by the Rochester Philharmonic, conducted by

composer Howard Hanson; Kaddish

was first heard at the Seattle Symphony 54 years later, with Gerard

Schwarz conducting cello soloist Yo-Yo Ma. This disc, like the first

release in the original Delos series, entered the Top 10 on the Billboard

Classical Chart of best-selling discs, and won accolades from

Gramophone and the Chicago

Tribune.

Despite over 50 years between them, the two ritual

works share a stoic sadness that reflects Diamond's take on the suffering

of the Jewish people. Psalm is

very dramatic, featuring huge slams of percussion and much modern-sounding

dissonance. The work was dedicated to André Gide, and inspired by a visit

to Oscar Wilde's tomb in Paris. Diamond met Gide shortly after he arrived

in Paris, maintaining a friendship that included the two of them playing

Bach, Chopin, and ultimately a four-hand arrangement of Psalm

on the piano.

Kaddish,

which Diamond terms his own “concept” of the traditional melodies of the

Hebrew Prayer for the Dead and of Hebrew cantilation, is quite poignant

and elegiac. Though Diamond wrote the work for Yo-Yo Ma at the urging of

Gerard Schwarz, Ma's contractual obligations to Sony resulted in the

substitution of cellist Janos Starker when the recording was made in the

Seattle Opera House.

In his 1991 interview, Diamond stated that he had

admired Starker's playing for years. “It was interesting, fascinating

even, to hear the differences in interpretations. Mr. Ma's was extremely

tensile, fervent; Mr. Starker's is mellow, deeply moving in its

expressivity, completely relaxed. I love both interpretations.”

The Symphony No. 3 was premiered in 1950. As in much

of Diamond's work, the opening Allegro deciso is marked by lots of forward

momentum and vigorous activity. The Andante's sweet, flowing sadness

culminates magically, transforming into a far more joyful Allegro vivo.

The final Adagio assai features lovely lyricism, with a beautiful elegiac

ending.

The second disc (Naxos 8.559157) offers Diamond's

Symphony No. 1 (1941), Violin Concerto No. 2 (1947), and The Enormous

Room Fantasia for Orchestra (1948).

Diamond's first mature symphony was written under the influence of his

teacher Nadia Boulanger (who seems to have trained just about every

notable American composer of Diamond's era); it was championed by

conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, who premiered it with the New York

Philharmonic Society in Carnegie Hall on December 21, 1941. The work

begins quite aggressively, transitioning into a graceful Andante and

majestic conclusion.

Though Diamond wrote the Violin Concerto No. 2 in

1947, it received only one 1948 performance until Gerard Schwarz triumphed

over legal entanglements to unearth it in 1991. This is a most beautiful

work, with flights of lyric fancy that prove quite irresistible. Violinist

Ilkka Talvi, currently concertmaster of the Mostly Mozart Festival

in New York's Lincoln Center, begins astringently, but settles in to

deliver an affectingly sweet performance, especially tender in the middle

movement Adagio.

Diamond describes The Enormous Room

as a lyrical symphonic “free-form fantasia” based on the snow scene in E.E.

Cummings' book of the same name. The work proceeds from what Cummings

terms “a new and beautiful darkness'” to a closing filled with “things new

and curious and hard and strange and vibrant and immense.” Like the Violin

Concerto No. 2, this is a beautiful work that deserves a place on today's

symphonic programs.

In the early 1990s, Delos was way ahead of other

labels in their mastery of digital recording technique. While today's best

engineering is more transparent and richer sounding, there is an

impressive amount of “air,” three-dimensionality and bass on these discs

that add to the joy of discovery.

|

|

|

Terry Riley: Cantos Desiertos

Alexandra Hawley, Flute

Jeffrey McFadden, Guitar

Naxos 8.559146

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

When a super-budget label eschews the tried and true

to issue the premiere recording of a work for flute/guitar duo by

California composer Terry Riley, the acknowledged “Father of Minimalism,”

it is time to take a listen. That the 25-minute Riley piece is framed by

four other attractive flute/guitar works, all by living American

composers, makes the disc essential listening for those drawn to this

instrumental combination.

Riley long ago progressed beyond his ‘60's period of

stoned-out repetitive minimalism to a more embracing, melodic style that

reflects 25 years of training and performance with North Indian classical

singer Pandit Pran Nath. Riley's long-time relationship with the

innovative Kronos Quartet, begun when he met violinist David Harrington

while teaching at Oakland's Mills College, has further expanded his

compositional palette. This diversity of influence – echt

California in its blending of the Far East with the post-psychedelic West

Coast avant garde – finds expression in the five flute and guitar pieces

that comprise Cantos Desiertos.

Cantos Desiertos

was commissioned by the Bay Area Avedis Chamber Music Series and guitarist

David Tannenbaum. While Tannenbaum is unfortunately absent from this

recording – he is most recently featured on Serenado

(New Albion), a delicious disc of guitar works by the late Lou Harrison

that includes Scenes from Nek Chand

written expressly for Tannenbaum and premiered by him at the 2002 Other

Minds Festival -- the Naxos performance is definitive by default because

the flutist, Avedis founder Alexandra Hawley, performed the premiere with

Tannenbaum at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San

Francisco.

The five Cantos Desiertos

are in turn part of the Book of

Abbeyozzud, a 26-piece work that

showcases the guitar either solo or in combination with other instruments.

Each piece has a Spanish title beginning with a different letter of the

alphabet. If this lends Cantos Desiertos

an inevitable Spanish flavor, the pieces also reflects Riley's love of

Indian music and jazz-like improvisation, and his unabashed pursuit of

joy.

Cantos Desiertos,

like many of Riley's works recently heard

at Berkeley's Edge Festival of California composers, is music that can

leave you cheering for more. The opening section, “Canción Desierto,” was

inspired by a dance-like melody Riley learned from his long time friend

and collaborator, Rajastani sitarist and composer Krishna Bhatt. The

movement bubbles along with great rhythmic freedom, only to metamorphose

into the subsequent “Quijote” (Dreamer). Things slow down temporarily with

“Llanto” (Lament), but pick up with “Tango Ladeado” (Tango Sideways). The

work ends with “Francesco in Paraiso” (Frank in Paradise), dedicated to

French composer and countertenor Royon le Mee, who died from AIDS at age

40. Lest this sound like a downer of an ending, the final movement began

as a piano and keyboard improvisation, while the preceding four works were

written during a sunny family sojourn to Puerto Vallarta.

Two of the other works on the disc, Robert Beaser's

likeable Mountain Songs and Lowell

Liebermann's Sonata were

variously commissioned by and dedicated to the flute/guitar duo of Paula

Robison and Eliot Fisk. Beaser's Mountain Songs, based largely on American

folk music melodies, is unfortunately short-changed in that only four of

the eight songs receive performances. Though Hawley and McFadden play

nicely, they pale beside the far more expressive duo of Susan Glaser and

Franco Platino, who offer the complete Mountain Songs

(Koch 3-7533-2 HI) on a 2002 release for which I wrote the liner notes.

Glaser/Platino play the beautiful opening “Barbara Allen” significantly

slower than their Naxos counterparts, rendering the song far more

evocative. On “The House Carpenter,” Platino's guitar is more incisive

than McFadden's, Glaser's flute more intense than Hawley's; only the Koch

team creates the unsettled feel that Beaser wishes us to experience. In

the final “Cindy,” Glaser rather than Hawley supplies the requisite swing,

with Platino's more closely recorded guitar more colorful than McFadden's.

The Naxos rendition is good enough to start your climb, but either Glaser/Platino

or Robison/Fisk will take you to the top of Beaser's oft-scaled opus.

New York City-born and Juilliard graduate Lowell

Liebermann counts among his teachers David Diamond. Liebermann was

nominated for the Prix Oscar Wilde by L'Association Oscar Wilde for his

opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray,

and received a Grammy nomination for his Piano Concerto No. 2,

Op. 36. Liebermann's two movement

Sonata for Flute and Guitar, Op. 25 proceeds from a dreamy Nocturne to a

highly energized, virtuosic gigue of an Allegro. Both performers rise to

the occasion.

[Those wishing to explore Liebermann's work will want

to experience the haunting mystery of his Sonata (1988) for flute and

piano. It is one of six works on American Flute Music

(Avie AV0004), a recital that pairs flutist Jeffrey Khaner with pianist

Hugh Sung. I hope to review this disc later on].

Joan Tower, recipient of the American Symphony

Orchestra League's first Made in America commission, contributes the

relatively short Snow Dreams.

Written for flutist Carol Wincenc and guitarist Sharon Isbin, the

intriguing piece becomes increasingly unsettled, metaphorically reflecting

the progression from light snowflakes to heavy snowfalls. The disc ends

with Peter Schickele's Windows: Three Pieces for Flute and

Guitar. While its conclusion gives

the instrumentalists a real workout, I prefer to hear Peter Schickele in

his other guise as P.D.Q. Bach. Regardless, for the other works on the

program – most certainly the Riley – this disc is more than worth the

asking price.

|

|

|

Harry Partch: The Wayward

Newband, Dean Drummond music director; Stephen Kalm, Baritone; Robert

Osborne, Bass-Baritone

Wergo WER 6638 2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

|

|

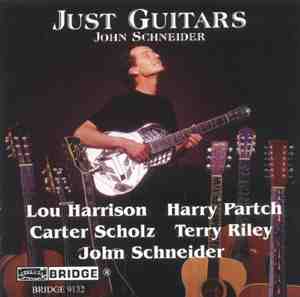

Just Guitars

John Schneider, Guitar and Vocals

Bridge 9132

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

HARRY

PARTCH: 20TH CENTURY MUSICAL ICONOCLAST

"The individual's "path

cannot be retraced, for each of us is an original being."

-- Harry Partch

Harry Partch (1901-1974) was a true original: an

enigmatic American composer, musical theorist, philosopher, instrument

builder, hobo, and artist who left a body of work both provocative and

perplexing. Not only did he (like his friend composer Lou Harrison) eschew

traditional Western tunings to explore just tonality and microtonaltiy,

but he also created dozens of fantastic instruments, mammoth dance/theater

extravaganzas, and unique musical narratives based on everything from

Greek mythology to his own experiences as a hobo.

Although little is known of the first 40 years of

Partch's life – when Lou Harrison suggested to Partch that he write his

memoirs, Partch replied that many of his early memories, especially of his

childhood, were too difficult to face – what Partch did say about himself

he documented in his works Bitter Music,

End Littoral,

U.S. Highball; a rare interview with

Studs Terkel; and passages recalling his childhood in the preface to the

second edition of his book Genesis of a Music.

The Wergo recording features performances by the

ensemble Newband. Formed in 1978 to explore music using microtonality and

alternative tuning systems, Newband in 1990 received custodianship of the

collection of Partch's original instruments for which Partch composed most

of his work. The ensemble's conductor, Dean Drummond, is both director of

the Harry Partch Instrumentarium and Professor of Music at Montclair State

University.

The instruments, all tuned to just intonation,

include the Chromelodeon I, a pedal-pumped reed organ with sub-bass

adapted to play all the chromatic pitches in Partch's 43-tone per octave

source scale; the almost seven foot tall Kithara II, a hybrid harp/slide

guitar consisting of 72 vertical guitar strings arranged in twelve rows

each with six strings; and other such exotically named inventions as the

Harmonic Canon, Bloboy, Diamond Marimba, Bamboo Marimba, Bass Marimba,

Cloud Chamber Bowls, and Spoils of War. The latter is a collection of

percussion effects suspended from a sculptural stand that doubles as

resonator, named for the seven brass artillery casings that are tuned to

fit step-wide in the space of a semitone.

The 43-minute disc features four pieces collectively

known as The Wayward, which Partch

described as “a collection of musical compositions based on the spoken and

written words of hobos and other characters – the result of my wanderings

in the Western part of the United States 1935-1941.” Originally created

between 1941 and 1943 and extensively revised through 1967, the works

exist in various arrangements, the last for Partch's expanded collection

of original instruments. The Wayward

includes the famed eight hitchhiker transcriptions of Barstow,

the San Francisco cries of

two newsboys on a foggy night, The Letter

depression message from a hobo friend, and the US Highball

transcontinental hobo trip.

All feature text superimposed over the exotic sounds of Partch's

instruments, with just intonation microtunings that seem to arise from an

alternative sonic dimension.

Vocal soloists Stephen Kalm, baritone, and Robert

Osborne, bass-baritone, variously recite and sing Partch's words with an

authoritative, out-there hobo accent. Short of a recording featuring

Partch himself, this is about as definitive as you can get.

The Bridge disc features guitarist and vocalist

Schneider performing 78 minutes of works written for guitar tuned to just

intonation. In addition to first recordings of three vocal works by Partch

– Letter from Hobo Pablo, December 1942,

and Three Intrusions,

all which consist of arrangements by Partch played by Schneider on Adapted

Guitar and members of Just Strings on Kithara and Diamond Marimba, the

disc includes works by Carter Scholz, Lou Harrison, Terry Riley, and

Schneider himself. Though the claim that Harrison's Scenes from

Nek Chand for steel guitar is a first

recording seems opportunistic – Harrison wrote the work for guitarist

David Tannenbaum, who premiered it at San Francisco's 2002 Other Minds

Festival of New and Unusual Music and released what also claims to be the

first recording on Serenado

(New Albion NA 123) virtually a month

after the Bridge disc reached my hands – the very fact of competitive

recordings of one of the last works from Harrison's pen is cause for

celebration. Schneider's vocals on the Partch works pale beside those on

the Wergo disc, but that he gives us first recordings of Partch

arrangements for adapted guitar is cause for gratitude.

What does one make of Partch's

autobiographically-inspired work? You may either find yourself fascinated

and impelled to play it over and over, discover yourself submerged in

another dimension, or dismiss it with a shrug. But one thing is certain.

In an age of mind-numbing uniformity and predictable musical formulas,

with popular “hits” increasingly predicted by sophisticated computer

programming and political rhetoric that seems a doublespeak variation of

same, those with open minds owe it to themselves to explore Partch's

genre.

Bob Gilmore, Partch's first official biographer,

asserts that while the composer is often described as a self-taught

“natural genius,” he in fact studied twice for brief periods in the early

1920s at the University of Southern California, where he took piano

lessons with the then well-known pianist Olga Steeb, and later briefly

studied harmony and piano at the Kansas City Conservatory of Music. While

Partch spent a number of years traveling around the country as a hobo, his

composing was done either during breaks from this traumatic existence or

after he had settled down. The eight hitchhiker inscriptions from a

highway railing at Barstow, CA that comprise Barstow,

the only completed composition from his traumatic hobo years, was

written in a few weeks of relative

peace after Partch took a trip in early 1940 in a “search for my soul.”

U.S. Highball was composed

in a room in Ithaca, NY, when he was working at a bookkeeping job for a

"small scrap iron company" some eighteen months after the hobo trip it

describes. (For more information, see

http://www.corporeal.com/, the

website produced by Danlee Mitchell, Executive Director of the Harry

Partch Foundation).

|

|

|

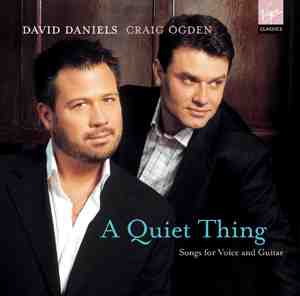

A Quiet Thing

David Danels, Countertenor; Craig Ogden, Guitar

Virgin Classics CDC 7243 5 45601 2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Though he has built his unprecedented international

career as an countertenor on the rare technical assurance and emotional

truth he brings to the rapid coloratura fireworks of Handel, Vivaldi and

other baroque composers, David Daniels is equally prized for the honeyed,

round tones that distinguish his introverted, legato singing. Nowhere can

the beauty of his instrument and depth of his interpretations be

appreciated more than on his latest CD, whose 19 songs consistently eschew

showiness for intimacy..

In a phone interview conducted right after David had

returned from grueling Paris recording sessions of Berlioz's Les Nuits

d'été, he explained the genesis of

A Quiet Thing.

“From the beginning of my career, I've tried to open

up the doors of repertoire for my voice type, broadening ideas as to

what's possible for the countertenor voice. I had already recorded two or

three Handel recitals, a couple of oratorios, an opera, and a song recital

with piano; I wanted to do something different.

“Originally the disc was conceived to consist solely

of American songs, but we changed the idea because the Virgin label is

based in Paris. The American songs I was really passionate about were the

ones I included: the Alec Wilder song, and then “Beautiful Dreamer” and

“Shenandoah,” which I like especially well with guitar.

“It's really important for me to maintain a sense of

musical integrity. I wanted it to be a very intimate disc, accessible not

only to the people who are fans of mine but also to people who don't

necessarily come to opera and classical music. But it isn't just a

collection of easy listening classical songs; there's substance to it. I'm

not going to sing music that I can't bring something unique to.”

This critic heartily seconds Daniels' assessment.

John Kander's “A Quiet Thing,” which opens the recital, is an ideal

vehicle for David's honeyed tone. It also establishes the feeling of

relaxation and peace which deepens with the youthful freshness of Alec

Wilder's gorgeous “Blackberry Winter” and Leonard Bernstein's gentle “So

Pretty.”

The Bernstein, with lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph

Green, consists of a dialogue between a child and his teacher. The child

questions the reasons we war against people far away, being told “they

must die for peace, you understand.” “But they're so pretty, so pretty”

responds the child. “I don't understand.”

While the song certainly strikes a chord, Daniels

explained that he chose it before the Iraq invasion scenario unfolded. “I

didn't have a political subtext in mind. I thought it was appropriate for

the boyish, white quality the countertenor voice can bring to it.”

Daniels next sings three Spanish songs from the 15th

and 16 centuries. The high tessitura of Francisco de la Torre's “Pampano

verde” especially benefits from the countertenor's soaring soulfulness; it

also displays his perfect legato. Ogden's well-recorded guitar punctuates

vocal phrases with an ideally artful smoothness. And Daniels' high note on

Gabriel Mena's “A la cara” is one to savor long after the performance has

concluded.

After familiar works by Dowland and Purcell, Daniels

sings three gorgeous Bellini songs. I must confess that I have often

considered the songs of Bellini and Donizetti inferior to their operatic

achievements. But with a singer of Daniels' (or Bartoli's) caliber, these

songs shine like gems.

I could have done without the treacle of Bernstein's

“A Simple Song,” and wish the Bach/Gounod “Ave Maria” were sung a half

step higher. But the simple beauty of Foster's “Beautiful Dreamer,” the

classic “Shenandoah,” and Martini's “Plaisir d'amour” provide a welcome

conclusion to a gorgeous disc.